- Home

- Sybille Steinbacher

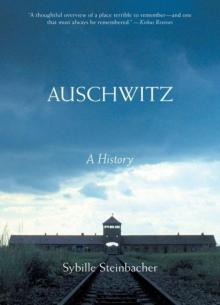

Auschwitz: A History

Auschwitz: A History Read online

Contents

Acknowledgments

That was Auschwitz

The subject

1 - The town of Auschwitz

2 - The concentration camp

3 - Forced labour and extermination

4 - Auschwitz the ‘model town’

5 - The ‘Final Solution of the Jewish Question’

6 - The extermination centre

7 - The final phase

8 - The town and the camp after liberation

9 - Auschwitz before the courts

10 - The ‘Auschwitz lie’

Published sources and selected eye-witness accounts

Further reading

Index of names

About the Author

Praise for Auschwitz

Copyright

About the Publisher

Acknowledgments

The original idea for this book came from Norbert Frei, whom I should like to thank for the opportunity to write it as an addendum to our major research project about Auschwitz, completed in 2000. I should also like to thank him for our many conversations and his critical look through the manuscript. Gabriela Gworek supplied me with information on the post-war history of Auschwitz, and Ulrich Nolte and Simon Winder took care of the book on behalf of the publishers. I am also particularly grateful to the three of them. The book is dedicated to my grandmother Johanna Seidl and her brothers and sisters.

That was Auschwitz

She lies by the wall, groaning. The prisoners in the Sonder-kommando, the special unit assigned to pull the corpses apart and empty the gas chambers, find her: a sixteen-year-old girl, covered with dead bodies. They carry her into an adjoining room and wrap her in a coat. No one has ever survived gassing before. On his rounds, an SS Oberscharführer notices the group. One of the prisoners pleads for the girl’s life: once she has regained her strength, please let her pass through the gate and join the other women on the road-building unit. But the guard shakes his head. The girl might talk. He beckons a colleague over. He has no hesitation either. A bullet to the back of the neck.

When the SS man yells at him, Stasio forgets to take off his cap as camp regulations demand. With a blow to the head the Scharführer hurls the young Pole to the ground and presses the tip of his boot to his throat until blood flows from his mouth. That evening Stasio’s comrades carry his corpse back to the camp on a stretcher. The Arbeitseinsatz (labour deployment unit) must always stay complete. There are nineteen living members and one dead one.

When Elisabeth is transferred to the prisoners’ writing room, her mother is still alive. Her siblings and her father are already dead. She loses thirty relations in Auschwitz’s gypsy camp, including her aunt and her five sons and daughters, and another aunt, only two of whose ten children survive. Her mother doesn’t survive either; she starves to death.

Numerous accounts and memoirs by prisoners in Auschwitz camp, like these brief summaries, have been passed down to us. They bear witness to the horror of events behind the barbed wire. The testimony of the victims is indispensable for any engagement with the subject of Auschwitz. It is only from their perspective that the scale of the crimes becomes properly apparent.

The subject

The history of Auschwitz is complex, and has not hitherto been the subject of a truly comprehensive work. This volume cannot fill that gap. Its aim is to represent the various aspects of the history of the Nazi concentration and extermination camp at Auschwitz in their most important contexts; to draw attention, within the wider perspective of political and social history, to the historical and political space in which the crimes were committed; and to sketch the sub-sequent history of the camp, including both the prosecution and punishment of the crimes after the end of the war, and the activities of Auschwitz deniers right up to the present day.

Auschwitz was the focus of the two main ideological ideas of the Nazi regime: it was the biggest stage for the mass murder of European Jewry, and at the same time a crystallization point of the policy of settlement and ‘Germanization’. It was here that extermination and the conquest of Lebensraum (‘living-space’) merged in conceptual, temporal and spatial terms. As a concentration camp, an extermination camp and the hub of forced-labour deployment, Auschwitz embodies all aspects of the Nazi camp system. The connection between the intention to exterminate and industrial exploitation became an immediate reality here. The fact that the city of Auschwitz, influenced by centuries of Jewish tradition, became a ‘German city’ at the height of the genocide draws our attention to the area beyond the confines of the camp, and raises questions of the public perception of the crimes committed there.

1

The town of Auschwitz

Centuries as a border town

Germans first moved to the area around Oświęcim in the late thirteenth century. They began a settlement project whose ‘completion’ almost 700 years later became the impulse for and goal of the Nazis’ brutal ‘Germanization’ policy’. Oświęcim, first mentioned in writing in 1178, lay on the dividing line between Slavs and Germans. Its name, derived from the old Polish święty, meaning ‘saint’, points towards the town’s early adoption of Christianity.

Medieval colonization of the east arose out of the desire on the part of Poland’s rulers to expand, to enhance Slavic culture through social, legal and economic systems, and thus bolster their power. The acceptance of German law –‘German’ being less a national than a legal term – was a peaceful assimilation process that maintained, respected and promoted Slavic traditions. The settlers introduced German municipal law, because by medieval tradition legal systems were tied to people rather than to territories; they established the laws where they happened to live, and they did just that in Oświęcim around 1260.

The town at the confluence of the Vistula and the Soła soon became a small trade centre; it was the seat of the court and the capital of the duchy that bore its name. Oświęcim switched political allegiances many times over the centuries: in 1348 it was incorporated into the Holy Roman Empire, and German became its official language. But with the first medieval agrarian crisis, the German settler movement came to a stop in the middle of the fourteenth century, the Hussite wars brought the colonization of the east to a halt, and under Bohemian rule Czech became Oświęcim’s official language. In 1457 the duchy – sold for 50,000 silver marks – came under the rule of the Polish crown, but temporarily maintained Silesian law before finally becoming a feudal possession of the Polish kings in 1565. When Prussia, Russia and Austria broke up the Polish state in 1772 and Austria annexed the areas between the Biała in the west and the Zbrucz in the east, including the great trading and cultural centres of Cracow and Lwów, the competing powers deployed their troops across the region, and in the same year Oświęcim passed into Austrian possession. German became the official language once more, the town bore the name Auschwitz, and it was in the new kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria, within the Habsburg Empire. In the wake of a new revision of the boundaries – the second division of Poland in 1793 and the third in 1795 did not affect the town –Oświęcim entered the German Federation after the Vienna Congress in 1815, and remained part of it until the Federation broke up in 1866. The town supported the Habsburgs until the collapse of the monarchy in 1918, and the Emperor bore the title ‘Duke of Auschwitz’ until the very end.

Catholics and Jews

Attracted by the trade routes leading towards Lwów (Lemberg), Cracow, Wrocław (Breslau) and Zgorzelec (Görlitz), Jews first settled in Upper Silesia in the tenth and eleventh centuries. It may also have been at this time that they moved to Oświęcim, which lay at the crossroads of the main routes, but their presence is first recorded in 1457. Unlike the surrounding towns, Oświęcim ha

d no law forbidding Jews to live and trade there. The Catholics did not unleash pogroms or carry out mass executions; they did not force the Jews to live in a ghetto, or drive them out of the city walls. During the first bloody wave of persecution in the modern era, the Chmielnitsky pogrom launched by the Cossacks in 1648–9, Jews were banished from the neighbouring towns, but in Oświęcim, perhaps because they were relatively few in number, they were left unmolested.

Unlike Prussia, which in the nineteenth century subjected the Polish inhabitants of the eastern provinces to unadulterated Prussian rule, Austria – under the pressure of political defeats abroad, and striving for reconciliation with Hungary – gave relatively free rein to the Galicians in their efforts to become Polish again and to achieve independent statehood. The Cisleithan crown territory of Galicia was awarded extensive rights of self-administration by the 1866 statute of autonomy. Poles took over the jobs of the Austrian officials, and the Polish language found its way back into the region’s schools and administration. Oświęcim reacquired its original Polish name, and the street names became Polish as well.

With the economic revolutions that were taking place at the same time, the ‘good Austrian era’ began for Oświęcim’s Jews. A number of decades followed in which the previously rather insignificant and poor Jewish community developed strongly in demographic and economic terms. The feudal and agrarian social order faded away, and with it went the old intermediary function of the east European Jews. Standing, as small shopkeepers, craftsmen, travelling salesmen, pub landlords and leaseholders, between the landed gentry, the peasantry and the state, they had been exposed to the corresponding social conflicts. This relationship, which had unfairly governed how Jews made a living and had for centuries denied them any economic advancement, disappeared. Jews were able to abandon their uncertain legal position, achieve complete equality as citizens, and exert considerable influence on culture and politics. A flourishing Jewish community emerged, and Auschwitz soon became an intellectual centre of orthodox Jews and also a site of significant Zionist associations. Even contemporaries spoke proudly of their own ‘Oświęcim Jerusalem’.

While Galicia remained an agrarian country at the end of the nineteenth century, with almost 80 per cent of its inhabitants making their living through agriculture, and with a great deal of unemployment and poverty, Oświęcim developed into a prosperous town because of its proximity to the newly developed industrial belt of Upper Silesia and north-west Bohemia. The industrialization process gained pace when the town acquired a railway station in 1856. Thanks to its location between the coal-mining area around Katowice (Kattowitz)-Dombrowa and the industrial area of Bielsko (Bielitz), Oświęcim became a railway junction in 1900: three lines of the Emperor Ferdinand Northern Railway led directly to Cracow, Katowice and Vienna.

While Oświęcim’s Catholics remained stuck in their agricultural jobs and rejected industrialization, only a small proportion of Jews continued working in their traditional trades. Most of them worked in the professions, particularly in the industrial sector. Many became big businessmen and opened banks and factories in Oświęcim and the surrounding area. Others even founded chemical factories and processing plants in the new industries. The oldest Jewish business was Jakob Haberfeld’s distillery, founded in 1804, which made the town famous for many miles around with its trademark ‘Schnapps from Oświęcim’.

Waves of immigration brought more Jews to Oświęcim than anyone else. By 1867 a total of 4,000 Jews had moved to the town, more than half the total of new incomers. Subsequently, the number of Jews came to exceed that of Catholic inhabitants. For a long time cooperation defined communal politics – although the Jews were expected to impose certain restrictions upon themselves. Only the post of deputy mayor was reserved for a Jew; the mayor was always a Catholic.

Before the Second World War the number of Germans and people of German descent in Oświęcim was insignificant. In the multi-ethnic Austrian state, and in the non-homogeneous Polish national state, the subjective sense of belonging to an ethnic group was defined by the language one spoke. In the censuses held during the Habsburg period the inhabitants basically spoke only Polish. In 1880 only one resident gave German as his spoken language, in 1900 there were ten, and by the time of the 1921 census three inhabitants gave their ethnic identity as German. No real German minority group existed in Oświęcim, even though, in the census of December 1931, 3 per cent of the population declared German ethnicity. Nor did the town have German schools, German organizations, German churches, German associations or German newspapers. But three editorial offices in the town published Polish newspapers; there were also Jewish papers, some of them in Yiddish, including the journals of several Zionist groups.

The construction of a camp

During the powerful wave of emigration that had swept over Galicia from the end of the nineteenth century, Oświęcim, on the country’s far western border, was the destination of thousands of new immigrants. They came to find work and a living as seasonal workers in nearby Prussia. They were known as Sachsengänger, literally ‘people on their way to Saxony’, a word derived from a Polish slang phrase used to mean ‘going to work’.

The town’s frontier location and the streams of migrants led to the building of a special camp in Oświęcim: the emigration camp for seasonal workers, with a national employment exchange. In October 1916 the town council sold the grounds, about three kilometres from the Old Town, to the Austrian government, and a year later the colony was adapted for emigrants and itinerant workers. But there were no barracks there, despite the fact that Oświęcim had served as a strategic base and military headquarters for the Austrian army in the First World War. The garrison was in Wadowice, about 15 kilometres away. The Sachsengänger camp consisted of twenty-two brick houses with hipped roofs, and ninety wooden barracks designed for 12,000 jobseekers. This was the barracks compound that the Nazis would transform into a concentration camp in 1940.

The Sachsengänger camp performed its function for about two years. After the First World War, when Oświęcim was part of the revived voivodeship of Cracow within the new Polish state, the employment exchange was quickly closed down, and the barracks passed into the hands of the state. It had various functions: part of it became a refugee centre for about 4,000 people fleeing Tešín (Teschener Land), the area between Oderberg and Bielsko, also known as Hultschiner Ländchen and the Olsa-Gebiet. Members of the Polish minority had fled from there after the area had been given to Czechoslovakia under the terms of the Versailles Treaty. In the former Sachsengänger camp the refugees set up a village with a school, an orchestra, a theatre, a sports association and a shooting club. A whole district came into being, called the New Town, or Oświęcim III (after the Old Town and the area around the railway station). Another part of the compound was rented by the state monopoly tobacco company, but most was requisitioned by the Polish army. One relic from the days of the Sachsengänger camp was the labour exchange, where a single office had survived in the barracks ground until the thirties.

In the wake of the border conflicts that broke out after the First World War, a referendum was held in March 1921, under the supervision of an inter-Allied government and plebiscite commission, concerning the territorial status of Upper Silesia. Oświęcim was not actually inside the area affected by the vote, but because of its proximity to the disputed territory the town was none the less involved in the border conflicts, because the neighbouring district of Pless was part of the plebiscite zone. During the three Silesian uprisings between 1919 and 1921 Oświęcim, which had been a centre of nationalistic and patriotic initiatives during the war, had become an outpost of armed Polish associations.

When the League of Nations Council, contrary to the results of the plebiscite, decided in October 1921 to divide Upper Silesia, giving two fifths of the land as well as the bulk of the industrial belt to Poland, the border crept further westwards. The part of Upper Silesia that had been Prussian and was now Polish was henceforth known in G

erman as Ostoberschlesien –‘East Upper Silesia’– a description that established the continuing German claim to ownership of the region. As a frontier town in the far west of the Cracow voivodeship, until the Second World War Oświęcim remained highly significant as a Polish army garrison and the administrative centre of the district of the same name.

In the years leading up to the Second World War social misery and wretched economy conditions affected Oświęcim along with the whole of Poland. While this put a strain on the ability of Catholics and Jews to coexist, it did not destroy it. But Jews did begin to feel they were being held at arm’s length. They were forbidden to use the bathing-place on the Soła, and access to the town park was closed to them. Jewish craftsmen received fewer commissions, and many of them were put out of work. Until the invasion of the Germans, however, the number of Jews in the town increased; at around 50 per cent of the population the rate was particularly high by the standards of western Galicia, which had a low Jewish population. Of the 14,000 or so people living in Oświęcim in September 1939 from 7,000 to over 8,000–figures vary – were Jewish.

The start of war in 1939

The keystone of the Nazi policy of conquest was the acquisition of ‘Lebensraum in the East’. Adolf Hitler planned a new base of German power that would last for centuries, with a solidly German ethnic storehouse. As early as 1925,in Mein Kampf, he had announced the aggressive thrust of his Lebensraum policy, and claimed that the taking of ‘the East’ was nothing but the taking of a legitimate inheritance to which Germany had always been entitled.

In the spring of 1939 Hitler had still considered using Poland in an ‘anti-Bolshevik campaign’ against the Soviet Union, and incorporating it into a satellite system under German leadership. But when Poland refused to accept the role assigned to it, in April 1939 he terminated the non-aggression pact agreed five years previously. Poland went from being a potential ally to a disruptive factor in the German push for expansion. Hitler’s policy became one of brutal aggression and unparalleled radicalism. Poland was conquered and politically destroyed, and was seen from that point onwards as a buffer zone against the Soviet Union.

Auschwitz: A History

Auschwitz: A History